Creating the Unexpected in His St.Petersburg Apartment

|

TEXT BY JOSEPH GIOVANNINI

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DEBORAH TURBEVILLE

In Russia, after perestroika, everything changed: Physicists became rug merchants. But for Andrei Dmitriev, a Russian philologist specializing in French language and literature, the transition to interior design was actually not so seismic, because, he says, he merely exchanged one text for another. "Linguists know that everything is a sign, and so I understood that you could read interiors as another system of signs, another text. When you enter a house, you can immediately judge who lives there, what circles they travel in. It's like fashion, where you tell character by clothes. I like semiotics: It makes many things clear."

By his own semiotic standards, however, Dmitriev is an enigma. His two adjoining apartments in St. Petersburg dodge consistency and mix messages. Each space exemplifies a different style that signals a different language.

"I have no formal training in design; that's why I can be weird and combine different things," remarks Dmitriev, a leading figure in St. Petersburg's emergent world of decoration. "But I was probably born an interior designer; I was making interiors from childhood. As a kid, I did my room in my grandmother's country house, and I built a little house when I was eight. I come from a family of artists, and I have always studied the history of art. I had a small antiques shop for five years. I just like beautiful things—what can I do?"

In 1990 Dmitriev bought a small apartment in a mid-19th-century building in the center of historic St. Petersburg, near Palace Square. In it he created a world that is the most formal and historically correct of the rooms he has designed for himself.

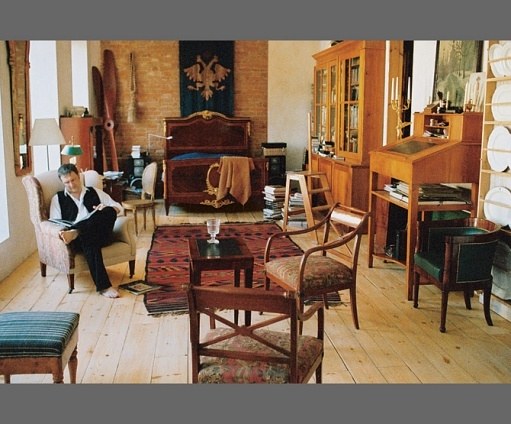

Hardly 500 square feet, the one-bedroom flat has a kitchen in a corner of the living room, but Dmitriev conjured the luxurious ethos of another time. "It's more formal because I was trying to re-create the ambience of the 19th century," he says. "I used only authentic late-18th- and 19th-century furniture, which I found mostly in St. Petersburg and restored in my workshop." He painted the living room ocher "because it's a 19th-century color" and the adjoining room bottle green because "it's very pleasant for the eye, and the space had to work as a bedroom, library and study at the same time." He mixed the colors himself from powdered pigments. For much of the decade he lived by candlelight.

In 1999 he bought a flat twice the size next door, and now his girlfriend lives in the smaller apartment and he in the larger. "It's kind of a convenient way to be together," he observes. The interiors of the newer, recently redecorated apartment do not allude to a different period in another century but simply evoke a sense of age. He surfaced all the walls in French plaster, a kind of gesso stained with natural products: The color of each room depends on whether he blended coffee, tea, tobacco, juices, rusty water or red wine in the mix. He surfaced the floor in the living area in wide planks of antique pine, and, in the bath, he laid down a timeless local limestone, set over radiant heating.

The 1,100-square-foot apartment, which had suffered an unfortunate renovation in the 1980s, had the luxury of two separate front rooms, plus a bath and kitchen. Counterintuitively, Dmitriev took down the walls separating the two rooms to create one long, multifunctional space that behaves like a loft but without looking contemporary. A Belle Époque bed anchors one end of a room otherwise furnished with antique chairs, secretaries and a lyre-form sofa. The rustic pine dining table and chairs in the open country kitchen, festooned with hanging copper utensils and antique bottles, has none of the polish of the more refined furnishings one room away.

"It's important for an interior designer to find a space to decorate, because when you're making things for yourself, you have complete freedom, and that opportunity doesn't come often," he says.

Though he does not pin himself down to a single style, he is really a specialist in an environmental charm bordering on the wistful. "In the second apartment, I was playing a lot," he says. "I made the doors to the kitchen into a pantry hung with old white plates. I created theatrical scenarios, draping curtains in the bath. I balanced opposites, to avoid becoming boring or kitschy."

For example, to offset the bourgeois quality of the bed (a 19th-century prop from the 1996 film version of Anna Karenina), he stripped the wall, bohemian style, to the raw brick and then hung a banner emblazoned with the czarist double eagle. "I'm not a monarchist," he says. "Sometimes I like to joke. I like to combine misery and luxury, poor and rich, modern and antique. I'm not really Russian in my point of view. I travel a lot and combine styles. Few people in Russia appreciate this approach, because they've never seen it before."

If in the first apartment he strove for authenticity, in the second he invented new combinations of old materials. Instead of gilding painted doors, he left pine doors natural and silvered the edges. He opened a wall between the bed area and the bath, so that while bathing in the antique marble tub, he could see beyond the bed and out a window to a nearby tree. He built a fireplace in the bath, luxuriously and decadently near the tub, and another in the kitchen, and both fireplaces can be seen roaring at the same time from the living area, where, interestingly, he did not create a fireplace. He upholstered the side of a wing chair in one fabric and left the rest untouched.

"I'm not really an eccentric," he says, protesting too much. "But it's boring to do what's already been done, and that's why I sometimes like to be eccentric. If I surprise myself, I know I'm surprising other people. My dream interior would be decorating a ruin with rich fabrics and some extraordinary pieces of furniture. That's really me. I may be the last Russian romantic."

Originally published: August 31, 2006 · Architectural Digest